A Great

Salt Lake City Forged Cover

The

following is an adaptation of an article, “The Case Of The Alligator Ink”,

that appeared in

Opinions VI – Philatelic Expertizing – An Inside View, published

by the Philatelic Foundation in 1992. The cover is believed to have been

manufactured by the master forger, Mark Hofmann.

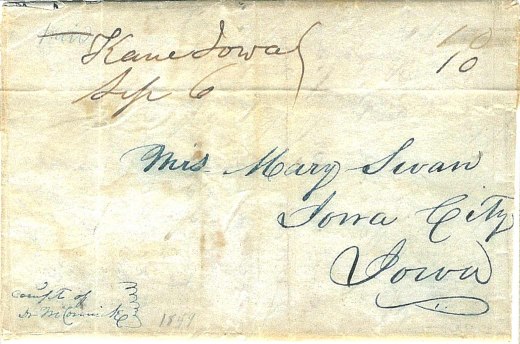

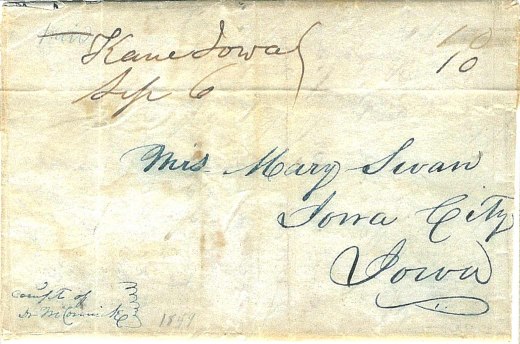

Figure 1

. An

1849 cover from

Great Salt Lake

City

to

Council Bluffs

,

Iowa

.

On

October 15, 1985, two bombs exploded in Salt Lake City

, Utah, killing two people. On the following day another bomb exploded injuring

Mark Hofmann, a well-known dealer in Mormon manuscripts and seller of the

so-called “Salamander” letter. On

January 23, 1987, after a plea bargain agreement had been reached, Mark Hofmann

pleaded guilty to two counts of second-degree murder and two counts of theft by

deception, including forgery. Articles have since appeared in various manuscript

publications regarding detection of some of the forgeries. A

cover, believed to have been forged by Mark Hofmann, was submitted to the

Philatelic Foundation for expertization in 1991.

The cover (Figure 1) addressed to Iowa, bears a “

G. S. L. City, Cal,

April 12, 1849” two-line postmark of

Great Salt Lake

City and is rated “40” in manuscript. The

marking was unrecorded prior to 1984 when a photocopy of the cover was

submitted, with impressive supporting evidence, to David Phillips for listing in

the 1985 edition of the American

Stampless Cover Catalog. The marking was subsequently listed under

California

, Utah

and Unorganized

Territory with an asterisk denoting institutional ownership.

The historical background will be examined first. Brigham Young, leading

a group of Mormons, began a permanent settlement in the Great Salt Lake

Valley

in September 1847. On

January 18, 1849

,

Great Salt Lake

City

was awarded a post office, under

California

jurisdiction, and Joseph L. Heywood was appointed postmaster. By

the end of February 1849 bimonthly mail service between

Great Salt Lake

and Kanesville (

Council Bluffs), Iowa

, had been approved but no contract to actually carry the mails was awarded. In

the interim until regular mail service could be established, private expresses

were sent out at irregular intervals under the direction of Brigham Young. A

mountain express man, Allen Compton, was employed to carry a mail express from

Great Salt Lake

to Kanesville in April 1849. Rather detailed information regarding this trip

exists because a journal was kept by Thomas Bullock, supervisor of this express.

Compton

left

Salt Lake City

on April 14, 1849

with nine other men carrying a total of 502 pieces of mail. The mail party

arrived at Kanesville on

May 26, 1849

, and its arrival was duly noted in the local newspaper on

May 30, 1849

.

The cover bears a two-line, handstamped postmark dated “

April 12, 1849 ” in a highly unusual type style. Dated two days prior to the departure of the

express to Kanesville, the date is certainly plausible. The

use of the unusual script type style is also supported by historical fact. On

January 20, 1849 , the first printing in the valley was performed by Truman

Angell, using the only type fonts available. He produced Mormon currency of

various denominations (Figure 2). It can be seen that the fonts used to produce

the currency are identical to those that appear in the postmark. The ink of the

postmark has a somewhat grayish cast to it and the individual letters of the

impression are slightly broken. The grayish cast is reminiscent of some modern

fakes produced using ink formulated without enough oil. However, a non-standard

ink formulation could be expected on such a usage, and the breaking up of the

individual letters is not uncommon on covers postmarked during the colder

months. There is no postmark offset on the reverse of the cover.

Figure 2

. Currency prepared using the same

style type font as found on the cover. Note

the signature of Thomas Bullock, supervisor of the express.

Next, attention was turned to the manuscript portions of the cover. The

cover is addressed to George A. Smith, Esq.,

Council Bluffs, Iowa. George A. Smith, a cousin of Joseph Smith, was a

prominent Mormon and is known to have resided in Council Bluffs in 1849. The

manuscript rate of “40” is more of an enigma. The ink, at first glance,

appears to be identical to the ink used in addressing the cover; and the rate,

for a cover carried east to Iowa, is unusual. The address is written in a

handwriting very close in appearance to that of Thomas Bullock, mentioned above

as being a secretary to Brigham Young, and involved in supervising the express.

His handwriting frequently shows letters drawn individually rather than

connected to adjoining letters and has a slant approaching the vertical. It is

not surprising, then, that the rate and the address are in the same hand.

The rate designation is the fist really troublesome feature of the cover.

Effective

July 1, 1845

, letters carried over 300 miles were subject to 10 cents postage. By the act

of

August 14, 1848

, letters from places on the Pacific

Coast

in California

to places on the

Atlantic

Coast

were subject to 40 cents postage. The other 1849 usages from Salt Lake City,

posted after contract mail service had been established, both bear 10-cent

rates. However, an 1850 cover is reported that does bear a 40-cent rate, it was

probably sent via

Panama

rather than overland. A 10-cent

rate should have been sufficient for carriage of the subject cover, in spite of

the fact that the Salt Lake Office was listed as California

for administrative purposes, because the mails were not carried via

San Francisco

and

Panama

to the east. The other possibility is that the “40” appearing on the cover

represents an express charge. A

40-cent express charge is reported to have been collected by A. W. Babbitt for

one of his 1848 express trips from Great Salt Lake, excepting letters “to the

poor, widows, and solider’s (sic) wives.”

An express charge, however, would almost certainly have been pre-paid

rather than collect as on the subject cover. No express fee due to a private

carrier would have been collected by the receiving postmaster.

Later in this article I’ll discuss what I think an express cover,

carried on the April 1849 trip, should look like, if one exists.

It is still possible that a governmental rate of 40 cents was charged,

but I consider it improbable.

The cover itself is noteworthy. It is of very pale brown paper and

homemade. The flap is affixed with a wax seal. It is not made from a single

piece of paper, as most are, one side flap being a separate cutout. The fact

that it is a cover rather than a folded letter is in itself bothersome. If

genuine, it would represent an early usage of an envelope, especially from the

Far West

. Envelopes did not see wide-spread

general usage until the second half of 1849. The very pale brown paper that the

cover is made from is almost exclusively associated with the period after 1853.

Figure 3. “Alligatoring”

of the ink of the “0” of the “40” manuscript rating.

The physical appearance of the ink, especially in the “40” rate area,

next drew special attention (Figure 3.). In this area there is a lightening of

the ink that is not consistent with interruption of the ink flow when the

numerals were fist written. It appears to the naked eye as though there was some

kind of chemical manipulation of the area, possibly from stain removal. The

cover was then examined under the ultraviolet, black light lamp (Spectroline

model B-100) to see if anything could be learned about the weakness.

Under the ultraviolet light all of the ink on the cover, including the

ink splotch at the right-hand edge of the cover, exhibited peculiar

characteristics. There was a

distinct hazing around each letter and a peculiar deep reddish coloration.

Both the front and back of the cover showed signs of a chemical treatment

but nothing exceptional appeared in the area of the weakness of the numeral that

would have indicated special treatment of the area. The fact that the ink

splotch at the right exhibited identical characteristics was a surprise. The

conclusion was that the ink of the splotch was the same as the other ink on the

cover. This provided the first real clue as to the true nature of the cover.

The cover has been opened at the right hand side and at the bottom. These

two edges are frayed in a manner which is distinctly atypical. The paper fibers

are still very fresh and not smoothed out as one would expect from a cover

opened over 100 years ago. The ink

splotch at the right edge, where the cover has been opened, goes completely

through to the reverse of the cover. The ink has stained both interior surfaces

and completely fills the paper fibers at the frayed edge. This finding indicates

that the ink stain occurred after the cover was opened.

If it had been stained prior to opening, one would expect to find some

paper fibers not stained. This fact is obviously not consistent with the fact

that the ink is the same as the other ink on the cover, supposedly applied when

the cover was mailed.

The preponderance of the evidence, at this point, indicates that the

cover is a forgery. However, because of the strong supporting historical

evidence, coupled with the fact that it was reported to have been found in a

archival holding, further examination using a microscope was performed. The

manuscript portions of the cover exhibited a peculiar cracking of the ink that

is not found when examining genuine writing of the period. This characteristic

is identical to that discovered by Bill Flynn and George Throckmorton when they

proved several documents sold by Mark Hofmann to be forgeries. This ink cracking

was aptly termed “alligatoring” by them. They proved that this phenomenon

was caused by the artificial aging of ink by duplicating the process in a lab

and observing identical results. This finding conclusively proved that the

patient cover is a forgery.

Now, having established that the cover is a forgery, I wanted to

determine if further evidence could be found that might shed light on how the

cover was manufactured. Two books regarding the Mark Hofmann affair, Salamander

by Linda Sillitoe and Allen Roberts and A

Gathering of Saints by Robert Lindsey, were consulted.

From these books and a partial transcript of an April 30, 1987, interview

with Mark Hofmann, conducted by R. Stott, a prosecuting attorney, and Brad Rich,

a defense attorney, much was learned about the forgery techniques used by

Hofmann. Forged documents, written in the hand of Thomas Bullock, are recorded;

and a most interesting exchange is to be found on page 465 of the interview

transcript.

Interviewer’s question: “Do

you remember if you ever had a stamp plate made by a professional engraver or

did you make them all yourself?”

Mark

Hofmann answer:

“I may have had a Salt Lake City postmark made professionally, as I

remember, but all of them dealing with these, that I am charged with, I made

myself.”

Figure 4.

A July, 1849 letter from

Salt Lake City

by express to Kane (Kanesville),

Iowa

. From the Floyd Risvold collection.

It might be worthwhile to

speculate, now, as to what a genuine folded letter carried on that

April 14, 1849

, trip might look like. I think that because the

Salt

Lake

post office did not have contract service, the item would most likely not have a

Salt Lake City

postmark. It is possible that because there was a postmaster appointment, it

would bear a postmark. In either

case, as the letter would have entered the mails at Kanesville, I would expect

it to have a manuscript Kane, Iowa, postmark dated between May 26, 1849, and May

30, 1849. Kane was the post office

name for Kanesville. It would most

likely have a 10-cent rate. Since the express was operated and paid for by the

Mormons in

Salt Lake City

, I think any express charges would have been paid for there, and I would not

expect any type of express endorsement to appear. A genuine folded letter, from

a July, 1849 Mormon express, which exhibits the characteristics described above

is shown (Figure 4).

Richard

Frajola (January, 2002)